(Reporting from Burkina Faso, David Rinck searches for our rock-'n'-roll roots in the landlocked shore of Africa.)

"Live, travel, adventure, bless, and don't be sorry." — Jack Kerouac

"Live, travel, adventure, bless, and don't be sorry." — Jack Kerouac

To a visitor today to these scrappy, drab concrete towns in the center of West Africa, it's hard to believe that just a century ago this was the epicenter of a magnificent and vital trans-Saharan caravan trade in gold and salt, stretching across the world's greatest desert. Linking Morocco and Mediterranean Europe with the gold kingdoms of the Gulf of Benin, and giving rise to mysterious and fabled cities that were centers of learning and culture, like Gao; Djenne (with its famous UNESCO World Heritage Grand Mosque); and Timbuktu, today the epitome of remote, it was where the Moors built one of Africa's earliest universities and a library famous throughout the Islamic world for its handwritten manuscripts and Korans.

Likening it to the shore of the vast sand ocean that is the Sahara, south of which lies the Bilad as Sudan, or "land of blacks" (Sudan, means "black" in Arabic), the Arabs named this part of the world the Sahel, or "shore" (the same root from which we take the word for Kenya and Tanzania's national language, Swahili, or "the language of the coast" — Saheli).

Likening it to the shore of the vast sand ocean that is the Sahara, south of which lies the Bilad as Sudan, or "land of blacks" (Sudan, means "black" in Arabic), the Arabs named this part of the world the Sahel, or "shore" (the same root from which we take the word for Kenya and Tanzania's national language, Swahili, or "the language of the coast" — Saheli).

These are the places my earliest heroes described in travel memoirs that I pored over in my pre-teen years, outstanding and intrepid men like Heinrich Barth, Gordon Liang, Mungo Park, and René Caillié, the first European to return alive from Timbuktu in 1828 (he collected a considerable reward for this feat from the Société de Géographie in Paris though he was denounced as a heretic because he had disguised himself as a Muslim).

And of course, Leo Africanus, who was born in Moorish Grenada and at age three watched Ferdinand and Isabella enter the city to crown the Catholic reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula and make refugees of his family, and who from his new home in Fez set out across the Sahara as a merchant with the caravans and lived for a short time at Timbuktu, and who later made his way to Egypt and wrote a vivid account of Cairo in the time of the Mamluk slave-sultans, and who drew the first map of Africa for the Papal Court after he was kidnapped by corsairs in Tunis and forcibly converted to Christianity at the Vatican, and whose story is so wonderfully told in Amin Maalouf's gorgeous novel "Leo the African." In my opinion, their journals were great, heroic works of adventure, and the wanderlust they inspired stayed firmly with me until I was finally able to follow in their footsteps.

And of course, Leo Africanus, who was born in Moorish Grenada and at age three watched Ferdinand and Isabella enter the city to crown the Catholic reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula and make refugees of his family, and who from his new home in Fez set out across the Sahara as a merchant with the caravans and lived for a short time at Timbuktu, and who later made his way to Egypt and wrote a vivid account of Cairo in the time of the Mamluk slave-sultans, and who drew the first map of Africa for the Papal Court after he was kidnapped by corsairs in Tunis and forcibly converted to Christianity at the Vatican, and whose story is so wonderfully told in Amin Maalouf's gorgeous novel "Leo the African." In my opinion, their journals were great, heroic works of adventure, and the wanderlust they inspired stayed firmly with me until I was finally able to follow in their footsteps.

As a young traveler in my early 20s, I retraced their routes to the Sahel and to the Sahara, beginning in Abidjan and trekking for months until I finally reach Dakar in Senegal. I lived on tins of sardines in the Dogon Country, rode a rice barge down the Niger near Mopti, and sipped mint tea by campfires with Tuareg nomads, the famous "blue men" of the desert. In Djenne, I haggled over daggers and ended up buying an Agadez Cross, a Tuareg talisman, from their tinsmiths or koumamas, and I slept in the Catholic mission in Segou and grooved to koras and balafons played by Griots (West Africa's musician caste).

This was never a destination for the faint of heart. I roasted in 120-degree-plus heat by day, and shivered through freezing nights on rooftops where I slept. I caught strep throat in Ougadougou and malaria in Bamako, and came home so emaciated that my mother screamed when she saw me get off the plane. Long ago circumvented by oceanic shipping and air freight, the Sahelian cities of the Saharan trade today are ghosts of their former selves, obsolete forgotten places in countries synonymous with poverty and hardship — Mali, Niger, Mauritania, Burkina Faso.

This was never a destination for the faint of heart. I roasted in 120-degree-plus heat by day, and shivered through freezing nights on rooftops where I slept. I caught strep throat in Ougadougou and malaria in Bamako, and came home so emaciated that my mother screamed when she saw me get off the plane. Long ago circumvented by oceanic shipping and air freight, the Sahelian cities of the Saharan trade today are ghosts of their former selves, obsolete forgotten places in countries synonymous with poverty and hardship — Mali, Niger, Mauritania, Burkina Faso.

Finally, in the mid-'90s, ethnic strife and the proliferation of automatic weapons have turned much of the Sahara into an anarchic no-man's land, and the fabled trans-Saharan routes — the Route du Tanezrouft, and the Route du Hogar, are pretty much off-limits today, decisively shutting down what little was left of the arteries that supplied these places with their lifeblood of commerce. All that's left is the romantic ring of their names to those that can find them on a map.

I have a distant memory from 2000, when I went to work in Benin in West Africa. I was on a plane (Air France), flying south from Paris to Cotonou. We crossed the Mediterranean in the afternoon and were treated to a gorgeous view of Algiers. Soon it was the indescribable Saharan sunset and nightfall over the desert near Tamanrasset, and finally as the sunlight faded completely, I could just make out the reflection of the moonlight on the Niger River, a thin silver thread shimmering far below me in the blackness. We had just crossed the Sahara, and I thought of all that huge world, all that history, culture and adventure, and all those mad explorations and ambitions, mine and many others. And, we'd just passed right over it all in a couple of short, irrelevant hours …

So what can an old punk rocker find in this impoverished corner of the former Afrique Francaise that links it back to the musical underground in SoCal? "Mali Blues" is something of a controversial term. There are the musicians themselves, like Sidi Touré, Afel Bocoum, Ballake Sissoko, Bassekou Kouyate, Boubacar Traore, Djelimady Tounkara, Kasse Mady Diabate, Oumou Sangare, Toumani Diabate, and most famously Ali Farka Touré, once described as the "John Lee Hooker of the desert."

Ry Cooder won a Grammy for his 1994 session with Touré entitled "Talking to Timbuktu," and Martin Scorsese once described Touré's music as "the DNA of the blues." Touré was ranked number 76 on Rolling Stone's list of "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time." The music is presented on numerous CDs, including the Putumayo "Mali to Memphis" compilation. But, without denying the strong ties, many of these Sahelian musicians doubt that their music is blues at all, citing blues as a purely American development, albeit of West African ancestry. In an interview Touré once stated, "They (the Americans) have got the branches and the leaves, but we've got the trunk and the roots."

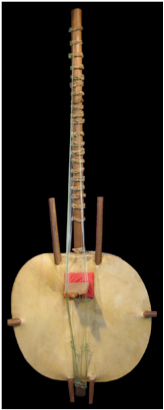

The trunk and the roots mostly comprise of the minor pentatonic scale, and the flat fifth or "blue note" that a great deal of Sahelian music shares with its American musical branches and leaves, as well as the "backbeat" rhythms of the ethnic groups in Mali, like the Songhai, Peul, Tuaregs, Bozo and the Bela. The n'goni, an ancient lute, the akonting, and the kora, or Jola lute, are tuned in such a way that the minor pentatonic is the most apparent scale, but also includes a "blue note", the same notes for which American musicians had to invent the "bending notes" in order to approximate the flat fifth.

As to rhythm, the akonting in particular is often described as the precursor of the American banjo, not due to its physical shape, but rather because of its plucking style, a finger-thumb pattern that creates a soft-hard-soft-hard meter — the "backbeat you can't lose" that Chuck Berry, Willie Dixon and others turned into rock and roll.

As to rhythm, the akonting in particular is often described as the precursor of the American banjo, not due to its physical shape, but rather because of its plucking style, a finger-thumb pattern that creates a soft-hard-soft-hard meter — the "backbeat you can't lose" that Chuck Berry, Willie Dixon and others turned into rock and roll.

On the other hand, one feature that is absent from the West African roots and trunk is the 12-bar I-IV-V chord progression. But then again, listening to the music of Lightening Hopkins, Son House and other traditional blues soloists, we are reminded that the 12-bar format was never universal, and in many cases the musician used to simply move along the I-IV-V progression as the whim took him, as he told his story. Finally, as in the western tradition, singers in West Africa tend to get the limelight, much to the chagrin of guitarists everywhere.

As described in the novel "Mali blues: Je chanterai pour toi" (Mali Blues: I'll Sing for You), a portrait of the life of Mali bluesman Boubacar Traoré, the blues in the Sahel has had to adapt in order to come to grips with modernity, but has tended to grow closer to its American cousin along the way. What was once a genre of music primarily concerned with work songs and family genealogy has increasing begun to deal with mainstay blues themes like affairs of the heart, love lost, and the treachery of women (a theme that seems to resonate equally well with West African and American men!).

Also, in a region that may contain the highest per capita population of musicians on earth, today the guitar reigns supreme. As a result, ironically legions of West African kids have been forced learn how to re-create the "blue note" and backbeat of their own ancestors on their six-string fretted imports, which can be heard in nightclubs, dance halls, and hotel lobbies across the region on any evening.

Also, like its American cousin, Mali Blues is essentially the real underground music of the Sahel. Imported hip-hop and rap are all the rage in the cities, and "blues is music that mostly old people like here," one young aspiring Burkinabe guitarist informed me. The image is of old men sitting under a tree somewhere in the countryside. One has to seek to find … so in October and September, stuck in Ougadougou, the capital of the nation of Burkina Faso, for a few weeks, I thought it would be an interesting project to find out what the underground was up to in the Sahel, or more specifically, to seek out Mali Blues.

Doamo Alassame's band at the Mecure Silmande is a pretty typical West African trio — guitar, bass, and a percussionist on jembes (African drums). When we talked, the old guitar player told me that yes, he had grown up playing blues, a skill he'd learned from his father. He also loved old American rock and roll, and like many of us that share this affinity, he'd grown up infatuated with the precious LPs his father had collected, especially Elvis, the Beatles and Johnny Cash. Though his tastes were eclectic, he preferred traditional music, both Western and African, but in order to earn a living at his trade, he'd had to adapt to many popular styles, again Western and African. On the other hand, the bassist and percussionist were young guys he lamented, and they play just popular styles. When he demonstrated a blues, the band drew clearly from the traditions and conventions associated with its American branches and leaves, rather than the indigenous trunk and roots (though he played a damn good lead).

MALI BLUES

The next day, I was wondering just what was the best way to go about finding Mali Blues in the chaotic motorcycle-clogged streets of Ouga. It was mid-morning, and I was sitting with my morning café and pain au chocolat in a park next to my hotel, strumming the blues on my own acoustic guitar. Suddenly, with the earnestness and openness typical of this part of the world, a young guy sat down next to me and grinned. "Vous jouez la guitare?" he asked. The invisible magic underground network that links all musicians all over the world had delivered me again. I had met Jean Noel Delwende Ouedraogo (or Delwende for short).

He told me that he was a guitarist himself. He had learned the guitar from his father, and knew how to play the Mali Blues I was seeking. He presented me with his CD "Sabaab" (for which I duly exchanged a copy of "Get Out" by the Cardiac Kidz). He had recently put it together with his group Majiji at Studio Baobab, one of the very few recording studios in the city. He explained that he liked rock and roll, and he wanted me to teach him more about playing it. So we struck a deal, he'd show me a few of his African blues songs, and I'd teach him a couple rock and roll numbers. In essence, an exchange of music that represented where the blues came from, for music that represented where it had gone.

Delwende dropped by the next day with his nylon string acoustic in an old gig bag, though steel string acoustic and electric is equally common. One of the numbers that I learned at our session was "Nechemba," which means, "respect for the elders" in the Mooré language of Burkina. It basically says that the experience that elders possess is a blessing, and youth should value it. It's not exactly blues as we in the States would recognize it, being a tune simply composed of open A minor and D minor chords finger-picked to a typical West African rhythm. I couldn't come close to his adept finger picking style, so I didn't try. Instead, rhythm guitarist that I am, I just strummed Am 7 to Dm 7 barre chords over it, with some picking on the minor pentatonic between his verses.

NECHEMBA

Other songs we played included a lament about armed conflicts in Africa (a major theme here) played over a driving Am-Dm-E progression. This one broke into a syncopated reggae meter at one point, reminiscent of some of Bob Marley's slower more soulful numbers like "So Much Trouble in the World", or "Crazy Baldhead" from Rastaman Vibration. It's notable in West African music that minor chords tend to take the place of the 7th chords that we use to play the blues in the West.

Another number we played was a haunting prayer-song to a local fetish, asking for intercession in the future because, as Delwende put it, "I don't know what's going to happen to me. I may be rich, or I may be sick, and one day we'll all die." This one featured a simple melodic I-IV-I-V progression in the key of G again with Delwende proficiently finger picking his way through the progression and adding nice little licks.

To fulfill my part of the bargain, I tried to teach Delwende some classic rock and roll and punk rock-oriented tunes like "Blitzkrieg Bop" by the Ramones, "Come On, Let's Go" by Richie Valens, and "Find Yourself A Way" by the Cardiac Kidz. But we quickly found out that he had as much trouble with the chord changes and arrangements in these tunes that I'd had with the finger picking in his. Rapid chord changes and bridges are very rare in West African music, with the local taste preferring simple even-measured cyclical progressions that put more emphasis on the rhythm, and give the percussionists and vocalists more range to improvise (think of "Sympathy for the Devil" by the Rolling Stones. I think it's the even measures of the progression, as much as the driving percussion, which infuses it with a West African "flavor"). We laughed, and he suggested that, "in America, you guys play better than us with your left hand, but we do better than you with our right!"

We finally settled on "What Goes On" by the Velvet Underground. Here it is, and here is a living example of the magnificent and enduring tradition that we are part of, and that connects all of us everywhere in the world, to our brothers and sisters in every culture from San Diego to Timbuktu, and that we should celebrate in the most joyous possible way everyday. Enjoy, and goutez le furie (babyface)!

WHAT GOES ON

— Dave Wallflower

Ougadougou (Burkina Faso), October 2010

More from Dave Wallflower:

- Play 'Misty' for me: BOMBAST rocks out at Bar Pink

- The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Punk Rockers from San Diego

- Blues Haitien and the Best Nightmare on Earth: Update from the West Indies

- Even Dave Wallflower gets the blues

- The Che Underground Cookbook: Dave Wallflower's Peri Peri Chicken

- We are all Blues Gangsters

As an eye-witness to the Oaugadougou terrace concert at the Hotel Ricardo Friday night, I have to say David Rinck, aka Dave Wallflower, was no shrinking violet, but instead, brought the house (such as it was) down in a wild jam-session with local Burkinabé musicians. The night air was sticky, the sky clear and the music African as David and his well-traveled Martin mixed it up with Delwende, a local 5-man African band. This observer was especially taken with the flautist who alternatively sang, yelled, spit, sneezed and actually blew notes on one of his numerous deep-red flutes. After two tough weeks in the Burkina Faso bush, this reporter welcomed the musical diversion – hats off to Mr. David. Bon voyage, my new friend.

Yeah David...great to see you and the Martin at work!!

More from Mr. Rinck's excellent adventure:

Nice write Dave...Did he ever learn "Find Yourself A Way"?

Brick by Brick 10/21 and Lestat's 11/04 hurry and come home son!

That was a great read,Dave,and some really nice music.Thanks very much for both.Look forward to seeing you back here.

I saw Honeyboy Edwards last night in Boston, he is 95 years old and playing the blues so bluesely, can I say that? You are an enigma David.

really kool

mali bluies

huh

i got the tamale blues

da-da-da-dah-da-de-dah-dah-de-dah//////

Extremely cool, Dave! I'm hoping you've planted the seeds for a soulful, finger picking, minor 7th-based African Ramones. Ouga Ouga Hey!

I've been away from the Che Underground far too long.

What a treat to come back and read such an informative and rich story.

David Wallflower-you are the Indiana Jones of The Che Underground! Its fantastic how you've gone on all these adventures and gleamed this knoledge and experience, and are able to share it with your humble Che kinfolk back home. This truly is riveting stuff!

Now if you could only learn to sing

: )

Dave is back! A rolling stone grovels no more! Dis dat ish, foo!

I agree with what Bobby says. Terrific writing and some really inspiring music.

Good work here....amen

Thanks dad!

Nice post Dave. Makes me think about music like this.