(An excerpt from Ray Brandes' saga of this 25-year-long collaboration. Read the full version in Che Underground's Related Bands section!)

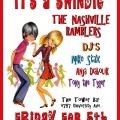

Editor's note: You can catch the Nashville Ramblers in their first appearances on the West Coast in 2010 the weekend of Feb. 5 and 6, when they’ll be appearing at the Tower Bar in San Diego (Feb. 5) and the Mind Machine in Los Angeles (Feb. 6). See you there!

Steven Van Zandt, guitarist for the E Street Band and host of “Little Steven’s Underground Garage,” once called it “one of the most unspeakably gorgeous instances of romantic yearning disguised as a pop song.” Indeed, the Nashville Ramblers’ song “The Trains” is a perfect piece of pop music: a once-in-a-lifetime convergence of thoughtful lyrics, exquisite melody and flawless performances by three of San Diego’s most celebrated musicians. The song, available on Rhino’s Children of Nuggets box set but until recently only found on an obscure late-‘80s pop compilation album, would be by itself enough to secure the Nashville Ramblers a place in the pantheon of great 20th century recordings.

Steven Van Zandt, guitarist for the E Street Band and host of “Little Steven’s Underground Garage,” once called it “one of the most unspeakably gorgeous instances of romantic yearning disguised as a pop song.” Indeed, the Nashville Ramblers’ song “The Trains” is a perfect piece of pop music: a once-in-a-lifetime convergence of thoughtful lyrics, exquisite melody and flawless performances by three of San Diego’s most celebrated musicians. The song, available on Rhino’s Children of Nuggets box set but until recently only found on an obscure late-‘80s pop compilation album, would be by itself enough to secure the Nashville Ramblers a place in the pantheon of great 20th century recordings.

Carl Rusk’s timeless anthem, however, only offered the world a brief glimpse of the vast talents of this undiscovered San Diego treasure. They have remained, outside of a small group of devoted fans, unknown and unappreciated. But a devotion to preserving the music they love, as well as an anger and disdain for the era in which they live, have driven them for more than 25 years.

The concept of a “supergroup” originated in the late 1960s with groups like Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young and Emerson, Lake and Palmer and quickly left a bad taste in the mouths of critics everywhere. A 1974 Time magazine article dismissed the phenomenon as an "amalgam formed by the talented malcontents of other bands." The Nashville Ramblers, while undoubtedly comprised of three of the most infamous musicians in San Diego '60s garage punk/rhythm ‘n’ blues, have always lacked the dueling egos, upstaging and musical infighting which often characterize such bands. Instead, the individual members of the band are lifelong friends who have formed the perfect musical as well as personal complement to each other.

All Good Things

Carl Rusk first began acting, then writing and performing professionally at the age of 12. His earliest musical projects were the Cavity Creeps, formed with Mark Zadarnowski of the Crawdaddys and his then-girlfriend Lydia Butinski; the Bogtrotters, with Joe Piper, Mark Zadarnowski and John Stoup; the Ideals, with Ray Brandes, Maure Silverman, Tony Paulerio and Paul Carsola; and the Hedgehogs, with Ray Brandes, Ron Silva and Paul Carsola. Carl had a natural musical inclination from an early age and applied himself with an intense dedication to becoming first an accomplished guitarist and later a singer and songwriter.

Carl Rusk first began acting, then writing and performing professionally at the age of 12. His earliest musical projects were the Cavity Creeps, formed with Mark Zadarnowski of the Crawdaddys and his then-girlfriend Lydia Butinski; the Bogtrotters, with Joe Piper, Mark Zadarnowski and John Stoup; the Ideals, with Ray Brandes, Maure Silverman, Tony Paulerio and Paul Carsola; and the Hedgehogs, with Ray Brandes, Ron Silva and Paul Carsola. Carl had a natural musical inclination from an early age and applied himself with an intense dedication to becoming first an accomplished guitarist and later a singer and songwriter.

Carl’s pre-Ramblers career hit a peak with the short-lived Mystery Machine, a band formed in the summer of 1983 that played a total of three shows: one in San Diego, one in Los Angeles and one in Orange County. The band was primarily a vehicle for Carl’s emerging songwriting talents, which found their place alongside folk-rock covers by the Byrds, Love, the Dovers and the Cryin’ Shames. “She’s Not Mine,” which appears on the second volume of Bomp’s “Battle of the Garage Bands,” was the only official release of the Mystery Machine. The group disbanded at the end of the summer when Carl moved to San Francisco to attend the San Francisco Art Academy.

The Crawdaddys, who were in the process of drawing their last breaths, arrived in the Bay area in early 1984 to record the tracks that would later comprise their “Here ‘Tis” album at Josef Marc’s studio in Berkeley, Calif. Carl skipped school to participate in each of the recording sessions. Former Hedgehog and Crawdaddy vocalist Ron Silva suggested Carl move back to San Diego to form a new group based in moody, folk-influenced pop.

Silva’s allegiance to early-‘60s beat and pop music is legendary. His name has become synonymous with the ‘60s revival he spearheaded in the late 1970s in San Diego, and he is respected worldwide as a singer and musician. His fidelity to detail, in total look and sound, had a big influence upon Carl’s own vision. Rusk’s relationship with Silva had begun on August 10, 1979, when the two met backstage at a Crawdaddys show at the Backdoor at San Diego State University. A growing friendship and mutual respect developed further as the Hedgehogs played countless gigs throughout 1981 and 1982. The two became constant companions, Ron staying at Carl’s parents’ house, and Carl joining Ron for several extracurricular Crawdaddys musical projects.

Silva’s allegiance to early-‘60s beat and pop music is legendary. His name has become synonymous with the ‘60s revival he spearheaded in the late 1970s in San Diego, and he is respected worldwide as a singer and musician. His fidelity to detail, in total look and sound, had a big influence upon Carl’s own vision. Rusk’s relationship with Silva had begun on August 10, 1979, when the two met backstage at a Crawdaddys show at the Backdoor at San Diego State University. A growing friendship and mutual respect developed further as the Hedgehogs played countless gigs throughout 1981 and 1982. The two became constant companions, Ron staying at Carl’s parents’ house, and Carl joining Ron for several extracurricular Crawdaddys musical projects.

Ron’s offer was the exactly the opportunity Rusk, who had grown a bit disconsolate on his own in San Francisco, was looking for. He missed playing music and was spending much of his time holed up in his apartment in the Haight, where he immersed himself in Bob Dylan and wrote the songs ”The Trains” and “No Other Girl.” Weekend visits to San Diego to record with the Mystery Machine and open for the Tell-Tale Hearts at Greenwich Village West did little to quench his desire to return to regular performing. “I knew I was kidding myself going to art school, and left San Franciso as soon as the school year ended,” he says.

That’s When Happiness Began

Upon returning to San Diego, Rusk joined Silva for a final couple of shows billed as the Crawdaddys, and began looking for other players to round out what would eventually become the Nashville Ramblers. It was decided that while they both were both multi-talented instrumentalists, Carl would play guitar and Ron would play drums. They experimented with second guitarists and bass players but were unable to find the perfect combination. “Eventually, Ron and I realized that our vision was just too specific to include anyone else,” recalls Rusk.

By this time, Rusk had amassed an impressive catalog of songs, drawing from his strongest influences: Paul Simon, Pete Townshend and the New York Brill Building composers like Gerry Goffin and Carol King, Ellie Greenwich, and Jeff Barry. Ron and Carl were living in the converted bar of the Maryland Retirement Hotel in Downtown San Diego on 6th Avenue and F Street. Walking home from El Indio’s one afternoon, the two were inspired to call their band “The Nash Ramblers.” According to Carl, “The mix of the word 'Nash' and the obvious car reference seemed perfect for our American/British style. Over time people began saying ‘Nashville’ instead of Nash on their own, and we just went with it. It was fine with us because it reminded us of the Nashville Teens.” The name also recalled Manchester’s “The Country Gentlemen,” whose name winked at a model of Gretsch guitars, and whose single “Baby Jean” predated the Rambler sound by 20 years.

The final piece of the puzzle was not at first an obvious choice. Tom Ward had already firmly established himself as a formidable bass player, first by joining the Gravedigger V in 1984 to give the group some much-needed musical credibility, and later through playing stints with Manual Scan and the Wickershams. Tom was a mere 17 years old, younger even than 18-year-old Carl, who was still considered a prodigy by many. But aside from his immaculate playing, Tom brought to the group a completeness that was both unexpected and welcomed by Ron and Carl. “Tom was eager, affable, and happy enough to be a part of what we doing to adapt himself to our vision,” Carl explains. “But perhaps more importantly, he shared our intense feeling of isolation from all other people — an inability to feel a part of any group, movement, religion or even family. This feeling of isolation is the glue that holds the Ramblers together. That and the sheer enjoyment of playing together.”

The final piece of the puzzle was not at first an obvious choice. Tom Ward had already firmly established himself as a formidable bass player, first by joining the Gravedigger V in 1984 to give the group some much-needed musical credibility, and later through playing stints with Manual Scan and the Wickershams. Tom was a mere 17 years old, younger even than 18-year-old Carl, who was still considered a prodigy by many. But aside from his immaculate playing, Tom brought to the group a completeness that was both unexpected and welcomed by Ron and Carl. “Tom was eager, affable, and happy enough to be a part of what we doing to adapt himself to our vision,” Carl explains. “But perhaps more importantly, he shared our intense feeling of isolation from all other people — an inability to feel a part of any group, movement, religion or even family. This feeling of isolation is the glue that holds the Ramblers together. That and the sheer enjoyment of playing together.”

Tom recalls that “Carl and Ron were looking to form a band out of their longtime, pre-existing association with each other, and after a trying out one or two other people, they settled on me for the bass "chair" — never quite finding a fourth — so the band became, and remained, a trio. I was glad to get into a group with these musically authoritative figures, who were also colorful characters with effortlessly distinctive personalities.”

Ward delighted in the opportunity to share the stage with such interesting and intriguing musicians. Silva, a world-class drummer, helped him become an even better bassist. “Ron could astound me with some crazy tom-tom fills and rolls, and he could sing at the same time. I learned my sense of time from him, so we are always together, as when there is a complete break or full stop in the midst of a tune,” Tom explains. “When we come back in, I know it's going to be right, because he is confidently masterful on "the tubs" as he used to jokingly refer to them — and at age 17 it was my job to figure out where he was going to be, and I learned to match the subtlety of his musical time instinct.”

It was also, however, Rusk’s unyielding and resolute musical integrity that attracted Tom to the group. “Carl is a perfectionist who wrote a song called ‘I Can't Compromise,’ but chose not to publish it, possibly because he felt it wasn't good enough as it stood and would thus be a compromise,” says Tom. “His shining star — the music itself, as he selects it — remains a source of wonder and an inspiration to him, and, by proximity, to those who know him and work with him in realizing at least a part of his vision and intent.”

The Nashville Ramblers play “The Trains.” Listen now!

Read the full Nashville Ramblers story!

— Ray Brandes

Also by Ray Brandes:

- Hallelujah! The story of Glory

- The Tokyos over San Diego

- The Hitmakers' hit that never was

- Sensational: The All Bitchin' All Stud All Stars and the roots of Country Dick Montana

- The Penetrators: Walking the Beat

- Dream Sequence: The history of the Unknowns

- Let the Good Times Roll: The untold history of the Crawdaddys

- The Zeros: I Don't Wanna Be a Hero, I Just Wanna Be a Zero

- Lend Me Your Comb: A short history of the Hedgehogs